Spruce Meadows, south of Calgary, where Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney was a marquee speaker for the annual Spruce Meadows Changing Fortunes Round Table

Wading into a national debate that was ignited by a controversial claim by Thomas Mulcair, leader of Canada’s left-leaning National Democratic Party (NDP), that Canada’s booming resource sectors harm the overall Canadian economy- the so-called ‘Dutch Disease’ hypothesis, Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney on Friday strongly rejected the notion and endorsed the view that high commodity prices are a net benefit to the Canadian economy.

The Dutch Disease argument Mulcair first put forth in April is that higher revenues from Western Canadian oil exports have increased the value of the dollar, which has made Canadian manufacturing less competitive in international markets, and that in the long-run, the contribution made by the resource sectors to the Canadian economy does not make up for the resultant decline in manufacturing.

In a presentation given to the annual Spruce Meadows Changing Fortunes Round Table near Calgary, an event that attracts business leaders from across Canada, Carney roundly dismissed the argument, saying “the [Dutch Disease] diagnosis is overly simplistic and, in the end, wrong.” He added that “Canada’s economy is much more diverse and much better integrated than the Dutch Disease caricature”, and that much of the decline in manufacturing is not related to the rising value of the dollar.

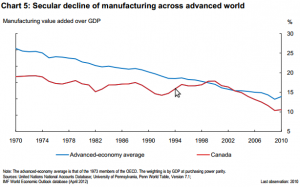

Carney provided the following chart to demonstrate that the decline in Canadian manufacturing’s share of GDP “is part of a broad, secular trend across the advanced world” as opposed to a Canadian peculiarity owing to the country’s natural resource wealth:

Carney said that an analysis done by the Bank of Canada using its Terms-of-Trade Economic Model (ToTEM) projects that the economic effect of a 20 percent increase in oil prices would be positive for Canada under all three scenarios modelled:

Stronger demand from the U.S. would contribute to a 3 percent increase in GDP over five years. Stronger demand from Asia, as is the case now, would boost GDP by 1 percent over the same time frame, and a short term supply shock would increase GDP by 0.2 percent in the first year.

Maximizing Returns

Carney said that to increase the benefit that Canada derives from high commodity prices, the country should shift “export markets toward fast-growing emerging markets”, in particular in the Asia Pacific region, as U.S. growth had slowed and would likely stay muted for the foreseeable future.

He also prescribed that the country build “new energy infrastructure—pipelines and refineries” to bring Western Canadian oil to Eastern Canadian consumers, who are now importing oil and paying an average premium of $35 over the price in Western Canada. The infrastructure would bring “more of the benefits of the commodity boom to more of the country”.

Other recommendations Carney made were:

- Improving interprovincial mobility through changes like standardizing occupational licensing across provinces, to help bring more skilled labour from other regions of the country to where it’s needed in Western Canada,

- Increasing skills of labour force by encouraging more graduates in the sciences, technology, engineering and math (STEM) and focusing “on skills upgrading and (re)training for existing workers”

- Increasing business investment in light of sufficient “precautionary cash balances” and “the scale of the resource opportunity”

Building on Canada’s Strengths

Carney concluded the talk by saying that the strength of Canada’s resource sectors should be recognized as “a reflection of success, not a harbinger of failure.”

He said that attempting to reverse the effects of Canada’s energy exports on the value of the dollar “requires that we undo our successes in order to depreciate our currency. Taken to its natural conclusion, this logic dictates that we shut down the oil sands, abandon our resource wealth, have high and variable inflation, run large fiscal deficits and diminish our financial sector.”

“Such actions would surely weaken the Canadian dollar, but they would also weaken Canada,” he added.

“In a world of elevated commodity prices, it is better to have them,” he concluded. “Rather than debate their utility, we should focus on how we can minimise the pain of the inevitable adjustment and maximise the benefits of our resource economy for all Canadians.”