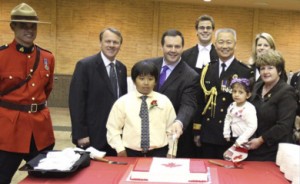

The Faster Removal of Foreign Criminals Act received Royal Assent on June 19, 2013, making it law in Canada (Steven W. Dengler)

The Faster Removal of Foreign Criminals Act has officially become law, making it easier to deport foreign criminals from Canada.

Canadian Citizenship and Immigration Minister Jason Kenney welcomed the grant of Royal Assent to the legislation:

“This new law will keep Canadians safer by ending endless appeals and loopholes that were being used by dangerous foreign criminals to delay their deportation, during which time many committed more crimes.

Canadians can now feel more confident in the integrity of our immigration system because violent criminals and fraudsters will be kept out while genuine visitors are welcome.”

The legislation amends the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act to:

- Make deportation of foreign criminals from Canada easier;

- Increase barriers to dangerous individuals entering Canada; and

- Reduce hurdles for non-dangerous visitors to Canada.

The legislation has received the support of several organizations, including the Canadian Association of Police Chiefs, the Canadian Police Association, and Victims of Violence and Immigrants for Canada.

Among the changes made by the legislation are limiting the access to the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB)’s Immigration Appeal Division (IAD) from foreign criminals, which CIC says will reduce the time criminals are able to stay in Canada by up to 18 months.

The Act also prevents foreign nationals who are deemed inadmissible on the grounds of being a threat to national security, being responsible for human trafficking or international rights violations, or being party to organized criminality, from appealing to remain in Canada under humanitarian and compassionate grounds.

Another change made by the legislation is the grant of new “negative discretionary powers” to the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration to refuse temporary entry even in cases when an individual has not been deemed a foreign criminal or inadmissible on the grounds of being a security threat or having involvement in human trafficking, international rights violations or organized criminality.

This power is the most controversial, as it enables a political party to refuse entry for political purposes. Many have charged the Harper government with doing this in 2010 when it initially refused to allow anti-war British MP George Galloway to enter Canada, based on accusations that his anti-war statements amounted to support for terrorism.

Kenney has tried to reassure critics that the new Ministerial power won’t be used in this way:

“We’re not looking at some broad, generalized power to prevent the admission of people to Canada whose political opinions we disagree with but rather those whose hateful attitudes, if given expression in Canada, could potentially lead to hateful actions or violence.”

Whether in years to come, the political inclinations of Canada’s ruling political party, whichever that may be, could bias their determination of what is a dangerous “hateful attitude”, remains to be seen.