Data from the Statistics Canada report on the income of immigrants, released in December, shows large differences in the economic performance of immigrants depending on which immigration program they were admitted through (Moxy)

In the second part of our series on the recently released Statistics Canada report on the income of immigrants, we delve deeper into the data and look at how various economic class immigration programs compare for immigrants who arrived between 1986 and 2010. The first part can be found here.

Among the most important immigration-related issues for the federal government every year is picking the right mix of immigration programs to make up the annual quota that it sets aside for new permanent residents.

The major priorities that the federal government seeks to meet in selecting the allocation are:

- meeting the humanitarian commitments it has set for itself to re-settle a certain portion of the world’s refugees

- accommodating Canadians whose family members live abroad and who they would like to re-unite with through family class immigration sponsorship

- admitting immigrants that will contribute to Canada’s economy and meet its investment and labour needs

To meet the last objective, the federal government currently allocates 60 percent of the permanent residence quota to economic class immigration programs, which consist of the Federal Skilled Worker Class (FSWC), the Canadian Experience Class (CEC), the business class programs, and the provincial nominee class programs.

Historically, the skilled worker program (FSWC) has contributed the largest portion of Canada’s economic class immigrants, but there have been calls to increase the proportion admitted through programs in the business and provincial nominee classes.

The provincial governments in particular have frequently called on the federal government to allow them to pick a greater share of Canada’s immigrants through their respective provincial nominee programs (PNPs), which has resulted in their quotas being increased from 2,500 in 1999, to over 30,000 in 2009.

Whether the FSWC should remain the mainstay of Canadian economic-class immigration or whether the PNPs, or perhaps business class programs, should continue to see their role expanded, is a question that the StatCan report can help answer.

The 30 year longitudinal study (we have only reproduced 24 years of it, as we assessed the data from 1980-1986 to be too limited to be useful) has a few surprising findings.

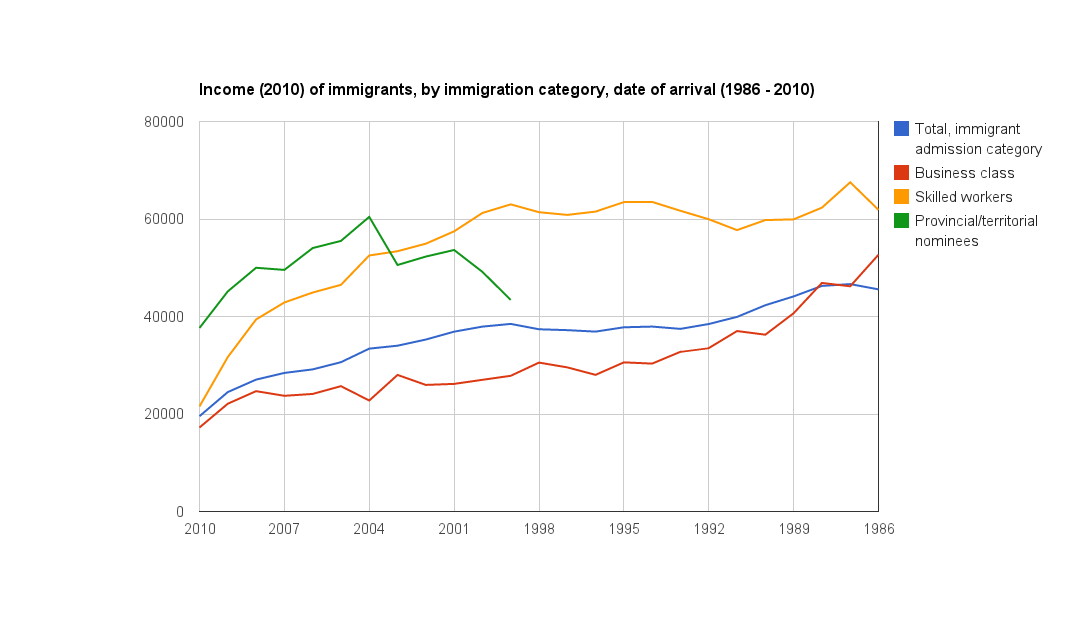

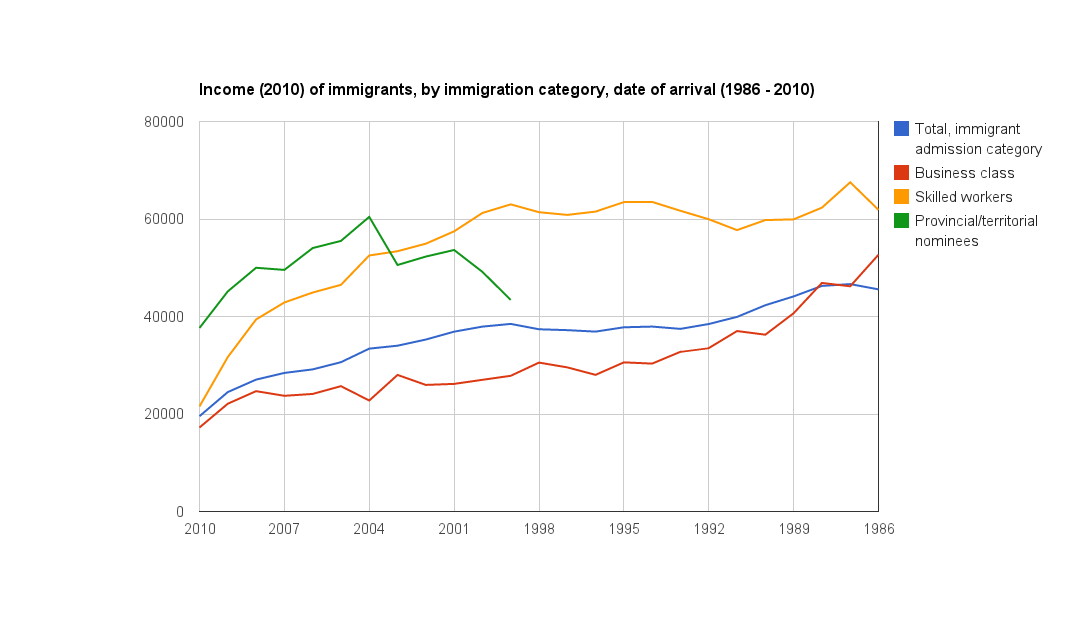

Income of immigrants by immigration program. Skilled worker class immigrants see the most wage growth over the 24 year period.

Early success for PNP immigrants, long-term success of the skilled worker class immigrants

Immigrants admitted through the FSWC earn significantly more than those admitted through the business classes, and after seven years in Canada, more than PNP class immigrants.

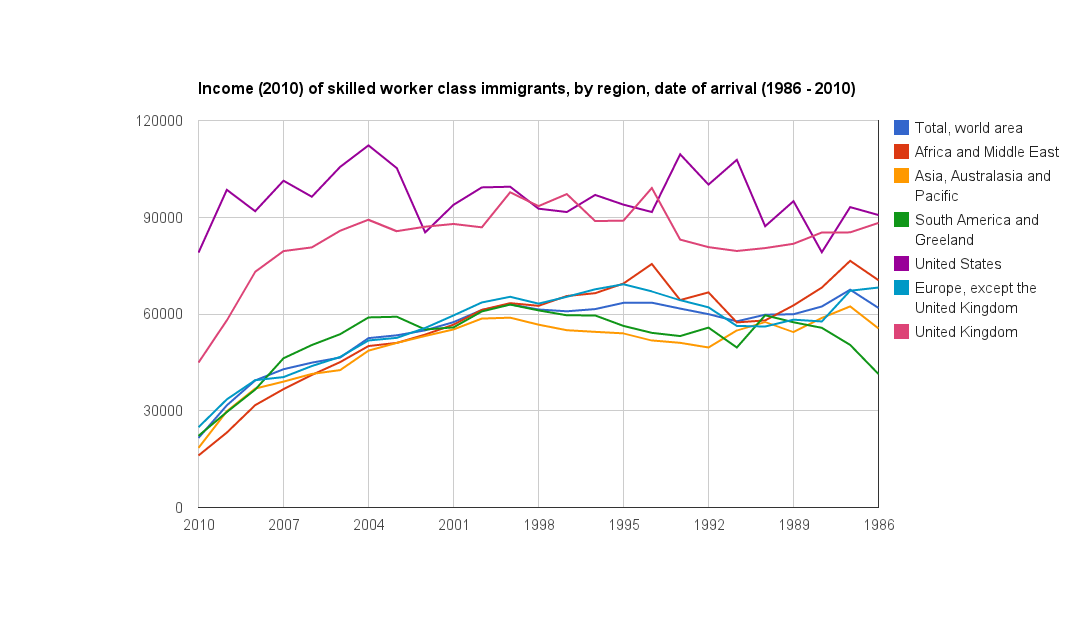

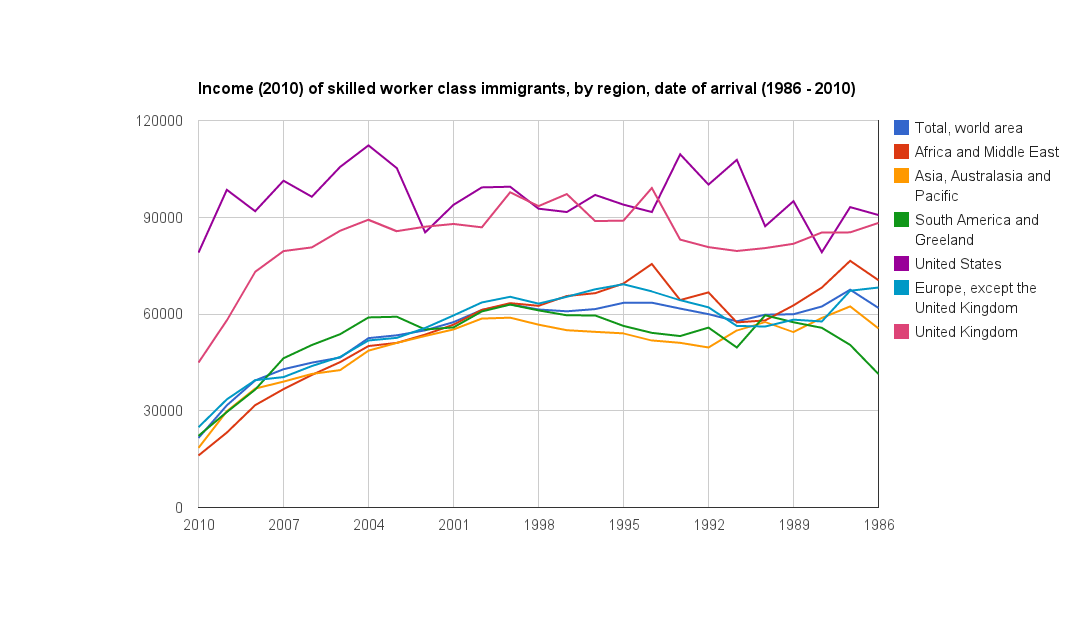

Average income in 2010 for skilled worker class immigrants. The graph shows rapid income gains in the first few years following immigration, followed by more gradual income growth

PNP-class immigrants earn nearly double what other immigrants earn in the first year of their permanent residence. This is most likely due to the fact that a person needs to already be in Canada and working to qualify for most provincial nominee programs, whereas immigrants who become permanent residents through the FSWC or business class programs arrive in Canada for the first time on the day they receive their permanent residency.

The data shows that the PNPs’ lead in income quickly closes, as FSWC immigrants see rapid income gains in their first few years in Canada.

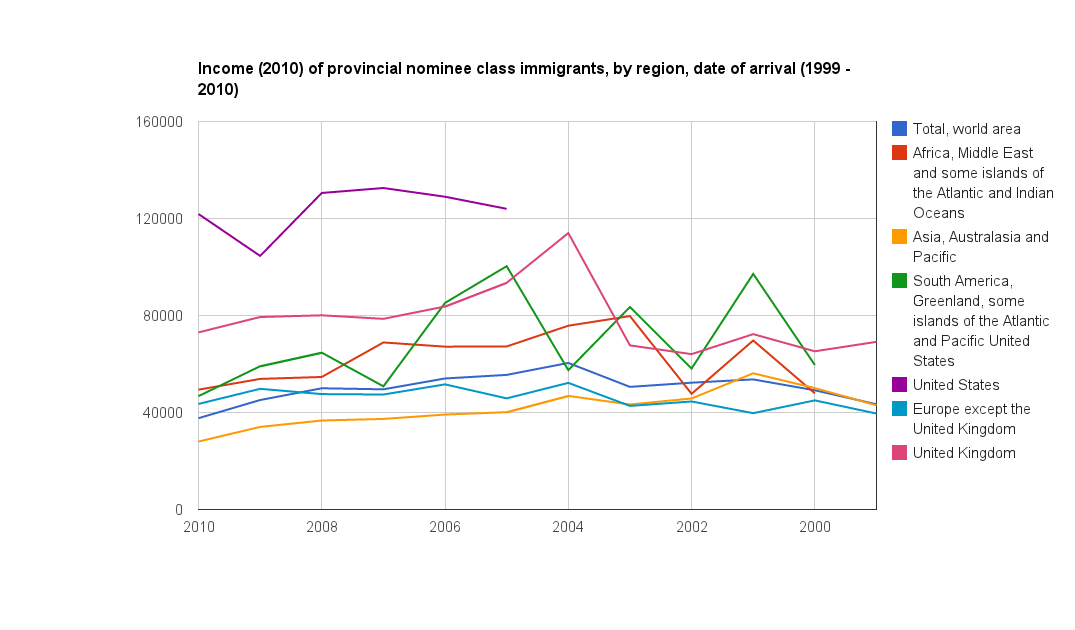

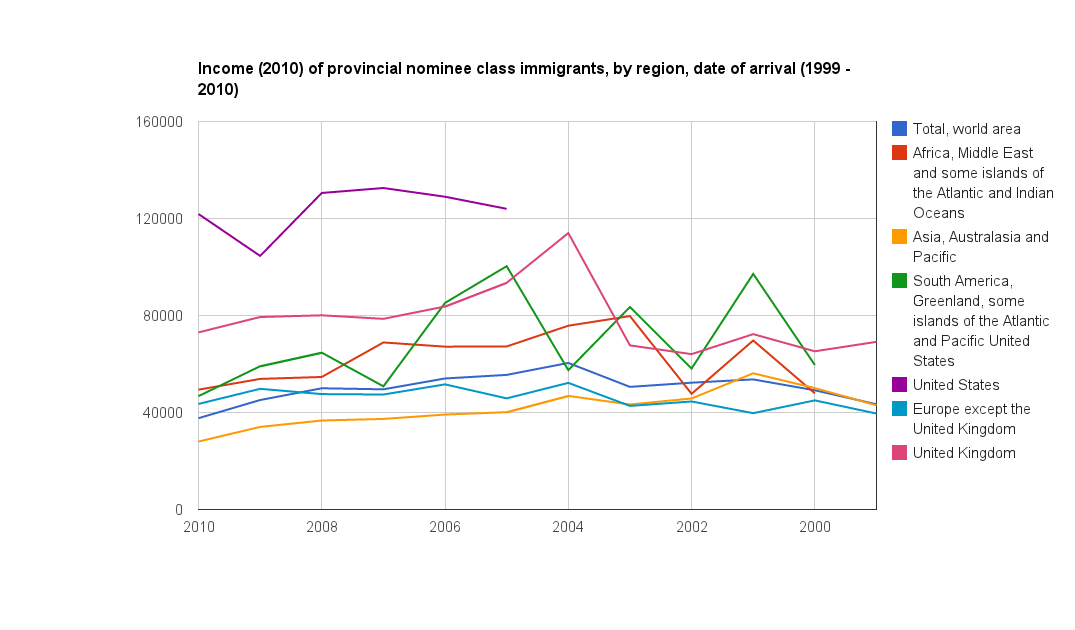

Average income in 2010 for provincial nominee (PNP) class immigrants. PNP-class immigrants start out with much higher incomes than other economic-class immigrants

It should be taken into account however that the data on PNP-class immigrants that arrived in the early 2000s is quite limited, given the provincial nominee programs admitted fewer than 10,000 immigrants for most of the first of half of the 2000s, so the long term income growth statistics for the PNP class could change over-time.

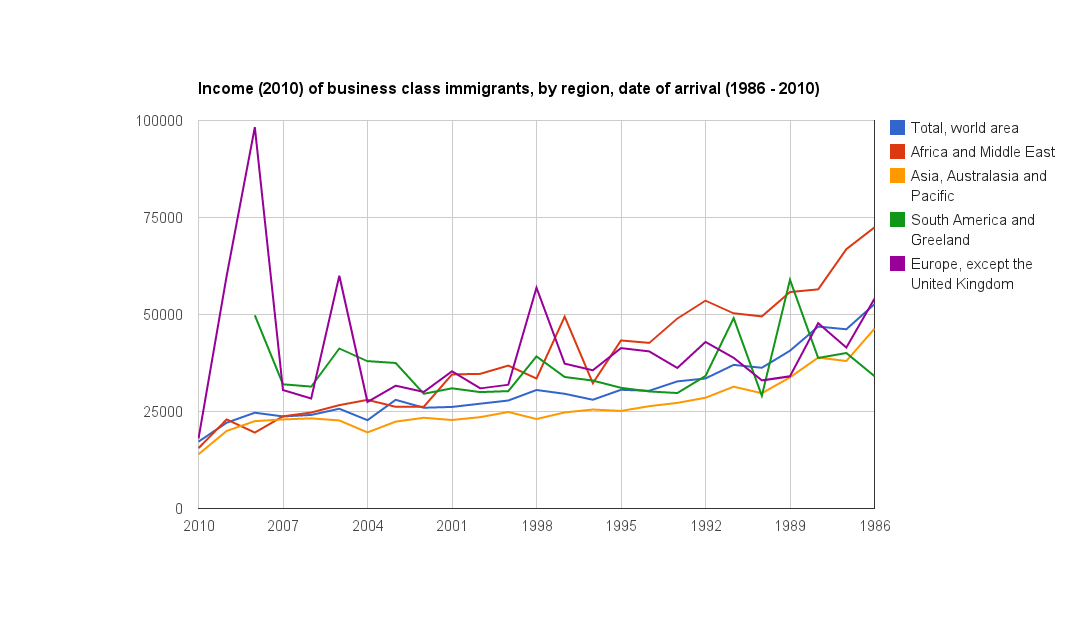

Poor performance of business class immigrants

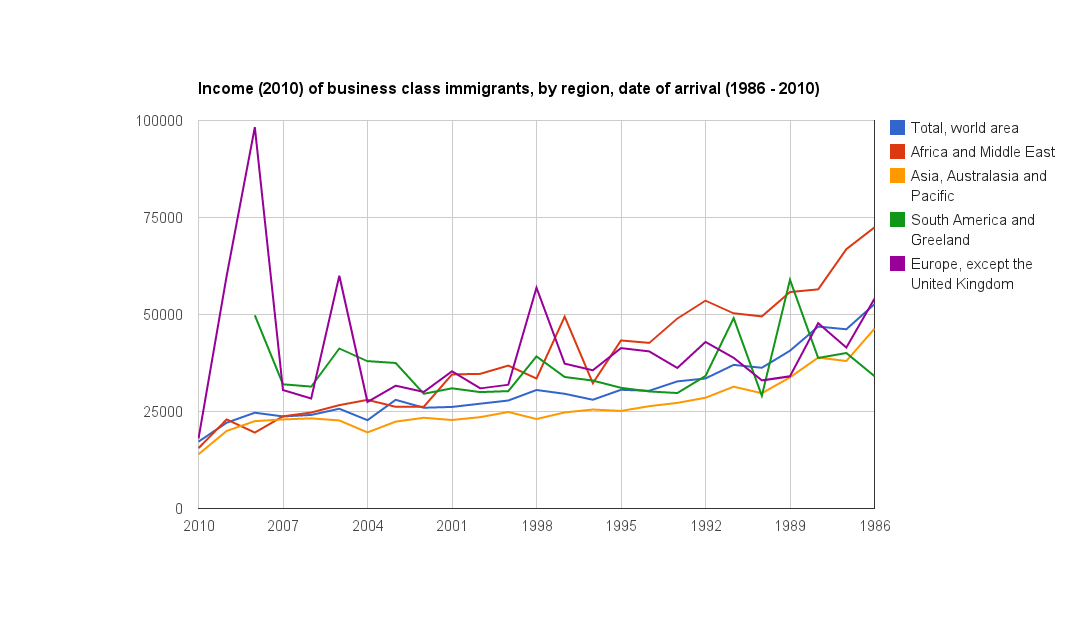

The business class immigrants, despite having met demanding minimum net worth requirements to qualify for immigration to Canada, have lower income levels than skilled worker and provincial nominee class immigrants, especially in the first few years after they arrive.

Over the long run, their income gradually converges with the skilled worker class, but this takes nearly 24 years and it never meets the level of their skilled worker counterparts.

One partial exception to this is immigrants from the Africa and Middle East region. Business class immigrants in this group see their income surpass skilled worker class-immigrants from the same region after 24 years.

Average income in 2010 for business class immigrants. Business class immigrants from the Africa and Middle East region see significant income growth over a 24 year period

Cause of business class under-performance

Ideally, business class immigrants, with their substantial capital and business experience, would be the biggest contributors to the Canadian economy among the country’s immigrant population.

One possible explanation for their lower than expected incomes is that they keep their investments abroad.

Canada, which has relatively high average personal income tax rates, is out-matched in investment opportunities by many regions in the world, like the rapidly developing Asian country of South Korea, which has average personal income tax rates and government expenditure levels that are one third lower than Canada.

While business-class immigrants could choose to remain invested abroad, skilled worker class immigrants likely benefit from working in Canada, since it is a high-income country that provides better wages than the vast majority of the world, and in any case they have few options other than working and earning their salary in Canada, since labour is not mobile like capital.

If investment opportunities in Canada being comparatively poor is in fact the cause of lower than expected income performance of business class immigrants, this is not a problem that the federal government can fix by changing immigration selection rules.